Violence and Liberation: The Characters and Readers of J.M. Coetzee

“…Exhausted, shivering, hands in their pockets to hold up their pants, whimpering with fear, swallowing their tears, having to listen to this coarse creature, this butcher…taunt them, telling them what would happen when the rope snapped tight…That is what Paul West, novelist, had written about, page after page after page, leaving nothing out; and that is what she read, sick with the spectacle, sick with herself, sick with a world in which such things took place…” (Elizabeth Costello 158)

In J.M. Coetzee’s novel Elizabeth Costello, Elizabeth Costello’s reaction after reading Paul West’s novel The Very Rich Hours of Count von Stauffenberg, demonstrates the level of difficulty an author has in dealing with the subject of violence. As Elizabeth Costello poses in the novel, “…she is no longer sure that people are always improved by what they read. Furthermore, she is not sure that writers who venture into the darker territories of the soul always return unscathed” (EC 160). Therefore, the readers of novels that engage with violence are left to grapple with how to interpret the violence they are encountering on the page, just as much as the author must determine what level of violence to engage with in his text.

Depending on how the reader wants to “read” Elizabeth Costello, the reader can extrapolate two conflicting issues in writing and reading about violence, and to what extent that violence should be explored. On one side, the reader can view the words and violence and action as that of the characters of the story. For example, Elizabeth Costello’s character is the one who has issues in dealing with the level of violence she encountered while reading West’s novel, and the thoughts reflected in the novel are viewed as hers. However, with regards to the treatment of violence and the characters in the novel, the author of the work complicates things because, even though the violence is happening to or in connection with the characters of the story, with possible added commentary from the narrator, it is –as is the case with all Coetzee novels- often times difficult to discern if the commentary is truly a reflection of the characters themselves or the author. The second issue that readers encounter in engaging with the violence of a novel is the affect it has on the reader himself. Like Elizabeth Costello’s reaction to West’s The Very Rich Hours… authors of novels who deal with varying levels of violence cannot anticipate how the readership will receive and be affected by the author’s treatment of violence to both the characters and the story as a whole.

Therefore, Elizabeth Costello comes to a point of contemplation about readers and writers engaging in violent texts, commenting that “She has begun to wonder whether writing what one desires, any more than reading what one desires, is a good thing” (EC 160). From the idea of reading and/or writing about violence as a “good thing,” I would like to push looking past reading/ writing about violence as a concept of good or bad, to viewing the engagement with violent texts as a liberating experience – not necessarily for good or bad, and not in the traditional sense of liberation from an oppressed state. But, rather, I would like to explore how J.M. Coetzee uses violence in his novels as a means to liberate both his characters and his audience from a state of innocence, thus pushing both the reader and the character – and quite possibly Coetzee himself – to a point of knowing. From this point of knowing, the characters, reader, and author all experience a growth and awakening to their humanness that requires all involved to take on a level of responsibility for the violence they’ve encountered.

Violence and the Character

Eugene Klerk contends “that Coetzee’s depiction of desire in his novels is directly linked with his ethical preoccupations; that in much of his work desire is shown to be a subjective window onto inassimilable alterity, loss, weakness and repressed or suffering aspects of being” (10). The desire of what Klerk is focusing on, or at least I interpret to mean, is Coetzee’s characters’ desires to discover what it means to be human in their respective state and/or states: white or black man, white or black woman, disabled person, etc.; in other words, Coetzee’s characters are in search of their human identity. As Trinh T. Minha-ha points out, in order to determine who or what they [the characters, the reader, the author] are, they must engage in a “search for an identity” that “is, therefore, usually a search for that lost, pure, true, real, genuine, original, authentic self, often situated within a process of elimination of all that is considered other, superfluous, fake, corrupted, or Westernized” (415). With regards to J.M. Coetzee’s works, his characters attain – or, rather, come to an understanding of – their identity through their engagement with the violence of the text; however, not only do his characters liberate themselves from a state of innocence – assuming that innocence is a relative state of ignorance – to a knowledgeable state of their identity relative to their experience with violence, but, the characters also discover the one unifying human quality that connects all of them together: subjection to physical pain.

Beginning with Coetzee’s first novel, Dusklands, J.M. Coetzee presents two different characters, each appearing to have nothing in common: they come from two different time periods, different locations and different circumstances. However, in both instances, each of the characters experience a common pathway towards achieving liberation, and through their experience discovers their own human reality. The first character of Dusklands is Eugene Dawn, a disgruntled, misunderstood research analyst for the Vietnam Project. Dawn views himself as “a thinker, a creative person, one not without value to the world” (D 1). However, Dawn feels marginalized by his boss, ‘Coetzee,’ an authority figure whom Dawn views as a “failed creative person who lives vicariously off true creative people” (D 1). Right from the beginning, J.M. Coetzee has presented a character, Eugene Dawn, who is trying to self-identify against his authoritative figure by proclaiming a difference between himself and the fictional ‘Coetzee’ in terms of creative genius. As Trinh would argue:

“Difference in such a context is that which undermines the very idea of identity, differing to infinity those layers of totality that form I…Many of us still hold on to the concept of difference not as a tool of creativity to question multiple forms of repression and dominance but as a tool of segregation used to exert power on the basis of racial and sexual essences.” (416)

According to her argument, and I agree, the exploration of difference, in terms of separation, to identify oneself, creates a sense of “otherness,” and by doing so, creates a sense of superiority over the other, thus resulting in domination and violence.

However, J.M. Coetzee shows that through Eugene Dawn’s life experience, Dawn is not entirely responsible for his need to create dominance over ‘Coetzee.’ As Victor Brombert writes, “…in Dusklands, the psychological-warfare specialist who conceives the apologia for political assassinations and terror operations confesses to having been a pathologically bookish child. “I grew out of books” (D 30)” (85). Brombert here is indicating that Eugene Dawn is a partial – if not dominantly – result of the books he has read throughout the course of his life. And Peter Knox-Shaw concurs that “The hypothesis that the private life is inextricable from the public one is carried in “The Vietnam Project” to the point of precise demonstration…and this would certainly appear to include a diagnostic link between the loss of affect Dawn displays in his personal relations and his work as a military propagandist.” (113). Even Eugene Dawn comments that “My human sympathies have been coarsened, she thinks [referring to the thoughts of Marilyn, his wife], and I have become addicted to violent and perverse fantasies” (D 9). Even though Dawn is expressing to the reader the thoughts of his wife, with J.M. Coetzee as the author, it is difficult to completely trust the narrator of his novels because it is always unclear if they are truly the thoughts of the character being represented, the narrator, or J.M. Coetzee himself. However, despite the uncertainty of who is making the claim within the story, I find Eugene Dawn’s personal reflections about his need for dominance over ‘Coetzee,’ and his wife Marilyn, and his son Martin, to be example enough that Eugene Dawn’s experiences are a direct mirror of the propaganda that he is analyzing for The Vietnam Project. Therefore, the sense of superiority over another is what propels Eugene Dawn forward into recognizing his own level of humanness as he proceeds through varying stages of violence – anger, aggression, and physical violence – to finally achieve liberation.

In establishing that Eugene Dawn feels a level of competence above his superior ‘Coetzee,’ Dawn begins to feel a level of hostility and anger towards his boss’s reaction about his writing, commenting that “It is unpleasant to have your productions rejected…The petty reaction of Coetzee to my essay is to be expected in a bureaucrat whose position is threatened by an up-and-coming subordinate who will not follow the slow, well-trodden path to the top” (D 5). So, not only does Dawn feel anger towards one he views as inferior, but he also views himself as exceptional, beyond the average. From this inflated ego, Eugene Dawn completes his plunge into liberation by kidnapping his son in a state of aggression, not towards his son, but rather his wife, Coetzee, even all who underestimate his abilities. From the enhanced levels of anger and aggression, Eugene Dawn falls completely into a psychotic state, stabbing his son before the police could intervene; therefore, resulting to physical violence – albeit, directed at a misplaced figure, his son.

Despite proceeding through the levels of violence, Dawn’s realization of his true being – his liberation from ignorance – doesn’t come until after he is committed to the mental institution. Eugene Dawn reflects, after all he is working through mentally with his doctors, that “I have high hopes of finding whose fault I am” (D 49). So, Eugene Dawn comes to the liberating knowledge that his identity is truly a reflection of all that he has experienced, ranging from his parents to the women from his past to the books he’s read throughout his life; all of these aspects in some way have compiled together to form who and/or what Eugene Dawn is, but it was only through the violent progression he followed that he was able to discover these ‘truths.’

Unlike Eugene Dawn, Jacobus Coetzee of the second narrative that is Dusklands, pursues a path of violence for liberation not in a need to fulfill his sense of superiority, but out of fear of losing his white identity; thus losing the identity I previously indicated Trinh as calling an “other” or “Westernized” perception of the self. Jacobus takes his black servant men with him on a journey into the interior of South Africa to explore the natives of the region. However, through a course of humiliating events, Jacobus is deserted by his black servant men, a great dishonor and humiliation for the white colonial settler; thus resulting in great anger towards his servants because of their undermining of his identity. Peter Knox-Shaw indicates that Jacobus may be lacking in what Trinh calls the “…real, genuine, original, authentic self” and therefore, his “…lack of an apparent self prompts him to view his identity as conterminous with that of the external world, “I am all that I see” (D 84); but in doing so he involves the entire universe in his sensation of nullity, his inner death. Hence his need for violence. For only by demonstrating his separateness – only by bringing death into the world – can he preserve a belief in the external life” (117). Taking Knox-Shaw’s argument a step further, I argue that Jacobus wanted to develop an identity beyond himself – he wanted to experience what it meant to be savage like a Hottentot or Bushman. And Knox-Shaw indicates this to a minor extent, saying, “Jacobus’ fear of losing racial identity in the wilderness remains latent all along in the anxious watch he keeps over his ‘tame’ Hottentots, since in their ‘betrayal’ he reads his own capacity for reversion to the wild” (112). So, as Knox-Shaw claims Jacobus hides his fear of losing his identity while he observes the Hottentots in their savage state, but I think it is only because he wants to learn what it means to let go of inhibition and be savage, not necessarily a fear of losing his preconceived identity, but rather an awakening to his inner, Hottentot identity.

And, I think, Jacobus accomplishes just as much. When he is abandoned by all of his servants, save Klawer, Jacobus begins the trek home. During his venture back to his settlement, though, Jacobus’ servant Klawer dies, and therefore, Jacobus is left to continue the journey homeward alone. During his final days, Jacobus feels more and more savage, partly due to his isolation and partly a result of his observations of the Hottentot tribe he encountered, and finally culminates into a completely psychotic state – much like Eugene Dawn – and Jacobus goes on a “day of bloodlust and anarchy…an assault on colonial property which filled me out once more to a man’s stature…” (D 99). As Robert Post reads the two psychotic break downs in Dusklands, he comments that “In Dusklands, the author pictures the oppressors, Eugene and Jacobus, as mad” (69). Although I agree they are mad, both characters do not start off as mad – as opposed to some of J.M. Coetzee’s other narrators like Magda from In the Heart of the Country. Instead, because of their human experiences and the events they go through to liberate from their state of innocence, I contest that Eugene Dawn and Jacobus Coetzee awaken to a reality of their humanness – a reality, of course created by J.M. Coetzee. As J.M. Coetzee presents it, they [Eugene and Jacobus] are subject to physical pain, even if they are the perpetrators of inflicting that pain. Therefore, they are a product of their own encounters with violence, and their progression, through violence, into madness acts as liberation – an awakening – to their humanity.

In the clip below, the character Giselle experiences a similar level of liberation when, through her experiences, particularly her developing relationship with Robert, while in New York City affect her overall sense of the identity she has known – that of a fairy tale figure from Andalasia. As becomes evident through the clip, Giselle realizes that her identity is being affected and she is liberating from her innocent state.

In addressing the issue of narrator/ author ambiguity, J.M. Coetzee’s Dusklands has elements of this ambiguity that create complications within the text for both the characters and the reader. And it is during the return trip of Jacobus back to his settlement that J.M. Coetzee presents the double death of Klawer – first drowning in the river (94) and then again being left to the elements due to illness and inability to carry on (95) – clearly complicating the author/ narrator distinction. Peter Knox-Shaw views this double death as being “…suspect that the disjuncture is intended rather to alert us to the ease with which a sole witness may falsify facts prejudicial to his self-presentation. In this case it is only the narrator’s obsessive interest in the pain of others that breaks down the reflexes of his defence” (111). However, we cannot ignore that the second narrative in Dusklands is narrated on multiple levels: J.M. Coetzee the author, the ‘translation’ from S. J. Coetzee who indicates in the afterward that the account he used to ‘translate’ “is the work of another man, a Castle hack who heard out Coetzee’s story…It records only such information as might be thought to have value to the Company…”, and the narrator Jacobus Coetzee himself (108). In the case of Knox-Shaw’s argument, I think he takes the narration of Jacobus Coetzee of the double death of Klawer too literal and fails to recognize the many ‘voices’ of the account. If anything, I think J.M. Coetzee is playing with the layers of ‘authority’ to indicate, again, that, with regard to violence, there are more layers of involvement than just that of the oppressed and the oppressor.

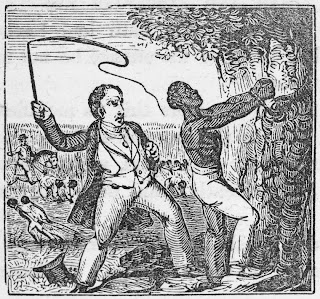

|

| A Man whipping another man tied to the trunk of a tree - 1862 |

The last episode of violence in Dusklands presents a recurring theme in many of J.M. Coetzee’s novels, in particular to his novel Waiting for the Barbarians, of questioning when is violence justified and when it is a means to assert or ascertain one’s identity. In the “Second narrative of Jacobus Coetzee,” Jacobus Coetzee continues a violent madness spree where he goes back to the native camp that his men chose to stay at and completely annihilates all of his men and the Hottentots in the camp that they have joined. I compare this last scene to Waiting for the Barbarians because, as Peter Knox-Shaw contests, the final execution scene of Jacobus’ defecting servants “would lack all credibility were it not for the act of defiance that incites their master to revenge” (118). Even though Knox-Shaw is speaking directly about the novel Dusklands, if you apply his idea more broadly to other Coetzee works, like Waiting for the Barbarians, the notion of death and violence lacking meaning unless performed under the context of retaliation completely ignores the idea of using violence as a means to exert pressure and force to achieve a desired level of knowledge. Assuming again that Jacobus is seeking to find his identity as a Hottentot, but still retain some aspect of his white, authoritative figure, we could view Jacobus as both the oppressor and the oppressed: oppressor because he is the colonizer, and therefore attempting to dominate the native inhabitants, and the oppressed because he experienced levels of violence and humiliation while residing with the Hottentot tribe. In doing so, Ali Behdad makes the claim, although applied more specifically to Waiting for the Barbarians, that “violence functions as a necessary component of eroticizing the colonized’s body and how such a notion of eroticism is crucial to the production of colonial rule” (201). Therefore, in examining the motives of Jacobus under the premise given by Behdad, the execution of Jacobus’ servants wasn’t just out a need for revenge, but also as a means for Jacobus to understand – to be liberated to an understanding – of what it means to be a true Hottentot.

Just as Jacobus tries to understand the ‘other’ or the ‘colonized’ by trying to become the other, J.M. Coetzee explores these same elements to a deeper level in his novel Waiting for the Barbarians. Unlike Dusklands, Waiting for the Barbarians is one continuous narrative presented by the Magistrate of an unknown colony at the edge of an undefined Empire. However, J.M. Coetzee juxtaposes the Magistrates actions and journey to liberation through violence with that of Colonel Joll, the Empire’s truth seeker, who does not necessarily reach a point of liberation from ignorance, so much as comes to a recognition of his own lack of understanding, but ultimately does nothing to grow from that realization. Even though both the Magistrate and Colonel Joll engage with violence differently throughout the novel, Ali Behdad points out that “for both Joll and the magistrate, the aim of colonial eroticism is to create a sense of political continuity by subjecting the colonized to a violent process of dissolution in which he or she is subsumed in the hegemonic power of the Empire” (202). In other words, both Colonel Joll and the Magistrate seek the same knowledge and understanding of the barbarians, even if their means – and motives – for achieving the information are different.

For Colonel Joll, the power of his exploration for what he calls ‘truth’ lies in the use of physical violence and torture. As Colonel Joll explains to the Magistrate,

“…I am speaking of a situation in which I am probing for truth, in which I have to exert pressure to find it. First I get lies, you see – this is what happens – first lies, then pressure, then more lies, then more pressure, then the break, then more pressure, then the truth. That is how you get the truth.” (WB 5)

Therefore, according to Colonel Joll, truth can only be achieved through a series of violent bouts of pressure, pressure applied to the point of breaking and then continued before any real ‘truth’ is revealed. Ali Behdad remarks that “Colonial “truth” is derived from corporeality and produced by inflicting pain on the body of the colonized; the surface of the other’s body must be violated to point of achieving the inner experience of “truth,” which would ultimately confer upon the colonizer a sense of continuity with his victim. The sacrificer is above all an interrogator who can hear the “tone of truth” in the material voice of his victims” (204). And, for Colonel Joll, the infliction of pain is the one unifying factor between himself and the barbarians he is questioning. As the Magistrate sums up from his discussion with Colonel Joll, “Pain is truth: all else is subject to doubt” (WB 5).

|

| Whipping Slaves, Missouri - Circa 1856 |

Unlike Colonel Joll, the Magistrate’s pathway to receiving ‘truth’ is not a physically violent or physical painful process, but rather more emotionally violent. Soon after Colonel Joll has left the colony, the Magistrate finds himself at the cell where Joll engaged in his torturous campaign against his captives. The Magistrate goes to the cell, more out of curiosity about what has happened to the barbarians brought in, instead of trying to help them. However, upon further inspection, the Magistrate comes to the conclusion that from actually seeing the torture cell, that “I know somewhat too much; and from this knowledge, once one has been infected there seems to be no recovering. I ought never to have taken my lantern to see what was going on in the hut by the granary. On the other hand, there was no way, once I had picked up the lantern, for me to put it down again” (WB 21). And, as Victor Brombert points out, “After such knowledge, there is no innocence. What the lantern allows him to see is nothing but violence, torture, humiliation, rape, mutilation” (83). The knowledge that the Magistrate received upon inspection of the torture room of Colonel Joll liberated him from his ignorant state, forcing him to recognize his own involvement in the violence perpetrated against the barbarians.

However, in pushing Brombert’s comment a little further, I find that the Magistrates liberation from innocence actually propels him further into a curiosity of and about violence. That is why he develops such a fascination with the Barbarian woman that he brings into his apartment and then proceeds to engage in a nightly ritual of washing her body from foot to head, but never seeks to sexual possess her. Instead, during the ritualistic washing, he spends most of his time inquiring about her torture experience, becoming frustrated at times that she won’t tell him all that he what he wants to know. According to Ali Behdad:

“The magistrate performs the ritual of washing the girl’s body in pursuit of secrets she is believed to withhold. But the washing of the tortured body is thematized as erotic, as the magistrate becomes engulfed in the pleasure of ablution. The body of the colonized provides the benevolent colonizer with the erotic vehicle for achieving the state of dissolution his counterpart achieves through torture.” (205)

Therefore the erotic behavior of the Magistrate serves the same purposes as torture did for Colonel Joll.

But, in contrast to Colonel Joll, the Magistrate comes to the realization that Behdad is describing. The Magistrate realizes that his “erotic behavior” is “indirect” because “…with this woman it is as if there is no interior, only a surface across which I hunt back and forth seeking entry. Is this how her torturers felt hunting their secret, whatever they thought it was? For the first time I feel a dry pity for them: how natural a mistake to believe that you can burn or tear or hack your way into the secret body of the other!” (WB 43). From the Magistrates realization, Robert Spencer extracts that “The motives and judgments that he ascribes to this recalcitrant figure are, he realizes gradually, nothing but projections, less insights or discoveries than, like the confessions extracted by Joll’s torturers, self-serving constructions of the truth that are actually produced by coercive interrogation” (182). Even though I agree with Spencer’s argument that the same ‘truths’ that the Magistrate is trying to extract from the Barbarian woman will come to no greater insight than that of what Colonel Joll achieved through torture, the Magistrates final observation that “to believe you can burn or tear or hack your way into the secret body of the other,” indicates that he has achieved a level of ‘truth’ regarding one’s ability to actually delve beyond the surface into the interior of another being. Therefore, I find that the Magistrate has commenced on an even deeper level of liberation from innocence because he is not only realizing his involvement in the violence, but is also becoming aware of how his involvement affects others – particularly the ‘others’ – involved.

The Magistrate’s true moment of transformation – his ultimate liberation from innocence into knowing – comes from his own physical experience of torture and pain inflicted upon him by the soldiers of Colonel Joll. As J.M. Coetzee writes, the Magistrate learns from his torturers about:

“…what it means to live in a body, as a body, a body which can entertain notions of justice only as long as it is whole and well, which very soon forgets them when its head is gripped and a pipe is pushed down its gullet and pints of salt water are poured into it till it coughs and retches and flails and voids itself…They came to my cell to show me the meaning of humanity, and in the space of an hour they showed me a great deal.” (WB 115)

For the Magistrate, his understanding of humanity comes as a result of experiencing pain. Ali Behdad points out that, “The Magistrate’s experience of pain through torture teaches him that his humanity does not reside in his principles, nor in his intellectual existence; rather, it is his body that defines his humanity…that the body is ultimately the site where the desire to dominate is articulated” (207). Robert Spencer presents a similar conclusion of Waiting for the Barbarians, writing that “Dehumanization staves off the moral horror that would stay the hand of the torturer or stop the mouth of his apologist if they were able to imagine the agonies suffered by their victims” (Spencer 178). Basically, by making the body of the colonized reflect a less human state, the colonizer can then dominate the physical body of the colonized, and therefore achieve his desired gain of power over the other. However, when placing Behdad and Spencer in direct conversation with one another, we come to the same conclusion that J.M. Coetzee’s Magistrate reaches: that those being tortured and humiliated are “MEN!” (117). Therefore, Spencer’s summation of J.M. Coetzee’s novel as “…the necessary corrective to torture: an egalitarian and unabashedly humanist moral code based on our shared vulnerability to physical pain,” is both poignant and profound (174).

Violence and the Reader

In the following clip from The Never Ending Story, Bastian is nearing the end of his experience in reading the novel called “The Never Ending Story.” However, the Empress character from the book reveals to Bastian in the movie that HE is partly responsible for the events that HE has just encountered through reading the story and engaging with the characters. Therefore, the destruction and violence experienced by Bastian through the text is, to some degree, of his own making.

Mike Marais in his article Violence, Postcolonial Fiction, and The Limits of Sympathy comments that “ Since violence is enabled by the symbolic order, responsibility for the violence is to be shared by all who participate in, generate, and are generated by, that order” (100). The symbolic order that Marais is referring to is the relationship among three varying levels of participation in the violence of a novel: the characters in the novel who are perpetrating the violence, the reader who is reading a novel and experience the violence of the text through language and words, and the author who is creating the violence for the characters and reader to engage with. In the previous section I have already examined the involvement of the characters and their responsibility for the violence in the text – or rather, how their experience with violence liberates them out of innocence to a point of some level of ‘truth’ about violence and their responsibility to that truth. Therefore, I now turn to examining the reader and their reaction to the violence they encounter textually. I will also examine how and why the author complicates the readers’ ability to engage with the violence of the text. Further, I will explore how, despite the reader’s reaction and the author’s complicating of the text, that the reader, through reading and mentally engaging with the violence in the text, is now a participant in the violence of the novel they have read and must acknowledge their liberation from innocence to a state of knowing.

As Marias has already established, there is a “symbolic order” that the reader, character, and author fall under as they engage with the violence of a text. For the reader, Mike Marais contends that readers must develop a level of sympathy for both the victim and the victimizers in order to maintain symbolic order. And I agree with Marais: J.M. Coetzee the author continually pursues the argument “…that the oppressor too is oppressed. Simply to hold him solely responsible for his crimes would be to dehistoricize them and so deny the symbolic context that enabled them” (Marais 101). Therefore, as the reader engages with the violence of the text, the reader must look beyond the victimization of the victims and recognize that the oppressors who are perpetrating the violence are just as much as a victim as those they oppress because the oppressor is a product of his own experiences with oppression; thus, the reader must “…sympathize with him and not just the victims of his oppression” (Marais 101). As previously explored, J.M. Coetzee presents this concept very keenly in Dusklands through the character of Eugene Dawn. Of Dawn, Robert Post writes that Eugene“…is a victim of his employers and the military…” but because of his experience with his employer and the military, “…the nature of his work turns him into an arm of the oppressor” (67). Therefore, it is the responsibility of the reader to develop sympathy for all characters involved in the violence of a novel, including those who appear as the oppressors.

In order to develop sympathy for all subjected to violence within the text, Marais argues that the reader needs”… to hear the stories of both [oppressor and oppressed]. The next question, then, is who tells the stories, and is there, in fact, a position in society from which both can be told?” (102). However, Brombert answers Marais' question by saying that “…even though the victors are doomed, the vanquished are forgotten; their voices have been silenced. History is written by the victors” (93). Now, even though Brombert is speaking specifically of history – or, rather, the narratives of history that we call history – all are written by the victors, by those who either survived or won. So, returning back to Marais’ question of “Who tells the stories?” the answer, according to Brombert is the victor – be that the oppressed or the oppressor – because the loser is silenced. In the case of J.M. Coetzee’s In the Heart of the Country, he attempts to write the novel from the perspective of the loser, Magda. Throughout the novel it is clearly evident that she is the loser to all oppression and violence she encounters within the text: her father’s death is played out multiple times and multiple ways, so the reader is never really sure if the father is actually dead, thus raising the question of Magda’s ability to actually kill her father; the rape scene between Hendrick and Magda is also presented in multiple ways, again leaving the reader to question the reliability of Magda; lastly, at the end of the novel she claims to be receiving lessons in Spanish from the ‘flying machines’ that fly over her head. All of these culminate, in other words, to present a novel by J.M. Coetzee from the perspective of the under-dog. However, J.M. Coetzee basically proves that by doing so it actually creates a character who is unreliable at best and whose account is viewed as superfluous by the reader because the character talks in circles and can be viewed as nothing more than crazy (not that we as the reader should not sympathize with Magda because she is crazy, but, rather, her craziness makes it difficult for the reader to take her reflections seriously).

Therefore, the perspective of the narrator of the story is an influential factor in how the reader responds to the text. The reverse is also true: the perspective and experience of the reader also influences how the reader reacts to the text. As Marais points out when the reader engages a text “…the reader has to do this from a predetermined position in the political dynamic from which he reads” (103). In other words, the author and the characters of the text cannot establish a preset position for all readers who encounter the text. The reader comes to the novel having had his or her own personal experiences that directly influence how the reader will receive the words on the page. However, Marais argues with himself, in relation to J.M. Coetzee’s novel Disgrace that, “The reader of Disgrace…has to sympathize despite herself, that is, notwithstanding the positions in the social dynamic that locate herself and her attitudes” because, as Marais contends earlier in his paper, “If one fails to do so [sympathize with all subjects of violence], one distances and thus exculpates oneself from the violence of which one reads” (104; 101). While I agree with Marais that the reader should sympathize with the characters, both oppressed and oppressor, of the text, it is impossible for the author to dictate how the reader will sympathize with the novel because the author and characters, again, have no way to influence the point of view that the reader has when they first come to the text, nor can the author anticipate how the text will be received upon completion.

Aside from not being able to completely anticipate the reader’s reaction to the violence in a novel, the author also has the hurdle of language to cross when presenting violence. Victor Brombert writes that “Coetzee’s indignation at violence (of which he himself never feels quite guiltless) is thus affected by a gap in every effort at genuine verbal communication” (85). Even though Coetzee explores varying degrees of violence within his texts, in order to push his characters development beyond the violence, as an author he runs into the issue of how to use language to present the violence to his readership. As Brombert is indicating, words cannot adequately express violence rendered within a text, particularly in a Coetzee novel where conveying violence through language actually creates a barrier for the reader’s reaction. Marais comments that the reason for that barrier is because:

“One of sympathy’s principal characteristics is precisely this irreducible tension between the body and language, in which language not only acts on the body but also the body on language. Being premised on this tension, my understanding of sympathy differs from rationalist conceptions of both it and empathy, which, in separating the subject from the object with whom she sympathizes or empathizes, run the risk of foreclosing the possibility of a corporeal interruption of the symbolic order [of violence].” (95)

While both Brombert and Marais present the same understanding that language obstructs the reader’s ability to truly appreciate the violence of a text, Marais is suggesting that the distance for the reader is a lack of bodily connection to the pain and suffering visually – through the written word – described on the page. Whereas, I think Brombert touches on an even deeper issue that readers encounter with a J.M. Coetzee text, the issue of authorial guilt. All of J.M. Coetzee’s novels grapple with violence to some degree, all of which, as Brombert indicates, Coetzee holds some level of contempt for the violence. However, and quite possibly this is what Brombert is hinting at, the indignation at violence may also reflect J.M. Coetzee’s own feelings of guilt about violence. For the reader, though, the words and descriptions of violence create a distance for the reader because not only are they unable to experience the bodily connection as Marais indicates, but the reader also cannot truly comprehend Coetzee’s guilt for the violence because, again, the reader is not experiencing the true order of violence or guilt that the words on the page are trying to convey.

I must disagree, though, that the reader cannot fully appreciate the violence they encounter from the written word. In returning back to Elizabeth Costello, Victor Brombert relates that, “The censorious Costello is” at least “honest enough to wonder what right she has to be shocked and to refuse to go on reading. She admits that after all she has done “the same kind of thing.” Costello’s honesty could be interpreted as Coetzee’s own oblique admission of guilt. His many fictional disguises point to his awareness of harboring a “dark” imagination” (83). We cannot ignore the fact that J.M. Coetzee the author grapples with some very difficult and often disturbing levels of violence in his texts. Much like Elizabeth Costello’s reaction to Paul West’s novel, the reader is exposed to the author’s dark interior when they engage with the violence of the text. But, the reader can identify with all of these aspects, despite a lack in physical experience with the violence on the page, because as Elizabeth Costello presents to Paul West, “We can put ourselves in peril by what we write, or so I believe. For if what we write has the power to make us better people then surely it has the power to make us worse” (EC 171). Thus indicating that what we as readers read directly affects us, and that the words, the language, the ideas, all of these aspects of a novel push the reader out of an innocent, ignorant state to a deeper (or higher, depending on the reader’s interpretation) of knowledge; a level of knowing that they must now decide what to do with.

|

| Photo by Jennifer Zwick |

Works Cited

"A man whipping another man tied to the trunk of a tree." circa 1862. Drawing. NYPL Digital

Gallery. New York Public Library. Web. 11 Dec. 2011.

Behdad, Ali. “Eroticism, Colonialism, and Violence.” Violence, Identity, and Self-

Determination. Ed. Hent de Vries and Samuel Weber. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997. 201-207. Print.

Brombert, Victor. “J.M. Coetzee and the Scandal of Death.” The Yale Review. 97.3 (2009): 81-

97. Literature Resource Center. Web. 15 Nov. 2011.

Coetzee, J.M. Disgrace. New York: Viking, 1999. Print.

---Dusklands. New York: Penguin Books, 1974. Print.

---Elizabeth Costello. New York: Penguin Books. 2003. Print.

---In the Heart of the Country. New York: Penguin Books. 1976. Print.

---Waiting for the Barbarians. New York: Penguin Books. 1982. Print

Enchanted. Dir. Kevin Lima. Perf. Amy Adams, Patrick Dempsy, James Marsden, and Susan

Sarandon. Disney, 2007. DVD

Klerk, Eugene. “The Poverty of desire: Spivak, Coetzee, Lacan and postcolonial Eros.” Journal

of Literary Studies. 26.3 (Sept 2010): 65. Literature Resource Center. Web. 15 Nov. 2011.

Knox-Shaw, Peter. “Dusklands: A Metaphysics of Violence.” Critical Perspectives on J.M.

Coetzee. Ed. Graham Huggan, et al. London: MacMillan, 1996. 107-19. MLA

International Bibliography. Web. 1 Dec. 2011.3

Marais, Mike. “Violence, Postcolonial Fiction, and the Limits of Sympathy.” Studies in the

Novel 43.1 (2011): 94-114. Project Muse. Web. 15 Nov 2011.

Minh-ha, Trinh T. “Not You/ Like You: Postcolonial Women and the Interlocking Questions of

Identity and Difference.” Dangerous Liaisons. Ed. Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti, and Ell Shohat, 1997. 415 – 419. Print.

The NeverEnding Story. Dir. Wolfgang Petersen. Perf. Noah Hathaway, Barret Oliver, and Tami

Stronach. Warner Bros, 1984. DVD

Post, Robert M. "Oppression in the Fiction of J. M. Coetzee." Critique 27.2 (Winter 1986): 67-

77. Contemporary Literary Criticism Select. Detroit: Gale, 2008. Literature Resource Center. Web. 15 Nov. 2011

Spencer, Robert. “J.M. Coetzee and Colonial Violence.” Interventions: International Journal

of Postcolonial Studies. 10.2 (2008): 173-187. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO.

Web. 15 Nov. 2011.

of Postcolonial Studies. 10.2 (2008): 173-187. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO.

Web. 15 Nov. 2011.

United States Military. Courtesy: Bill Van Eck. "US Leaflet: Vietnam War Propaganda." January

1966. Photograph. 15th Field Artillery Regiment. Web. 11 Dec. 2011.

"Whipping Slaves, Missouri." Circa 1856. Drawing. Slave Sales and Brutality. Web. 11 Dec.

"Whipping Slaves, Missouri." Circa 1856. Drawing. Slave Sales and Brutality. Web. 11 Dec.

2011.

Zwick, Jennifer. "Visual Studies Reader." n.d. Photograph. PBWorks. Web. 11 Dec. 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment